Literature Review on Healthy Eating Habits for Adolescents

- Research commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

Influences on eating: a qualitative study of adolescents in a periurban area in Lima, Republic of peru

BMC Public Health volume 16, Article number:40 (2015) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Peruvian adolescents are at high nutritional take chances, facing bug such as overweight and obesity, anemia, and pregnancy during a period of development. Research seeking to understand contextual factors that influence eating habits to inform the evolution of public health interventions is lacking in this population. This study aimed to understand socio-cultural influences on eating among adolescents in periurban Lima, Peru using qualitative methods.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews and pile sort activities were conducted with xiv adolescents fifteen–17 years. The interview was designed to arm-twist data on influences on eating habits at four levels: private (intrapersonal), social ecology (interpersonal), concrete environmental (community settings), and macrosystem (societal). The pile sort action required adolescents to identify cards with food images into groups and then to describe the characteristics of the foods placed in each group. Content analysis was used to identify predominant themes of influencing factors in interviews. Multidimensional scaling and hierarchical clustering analysis was completed with pile sort data.

Results

Private influences on beliefs included lack of financial resources to purchase food and concerns about body image. Nutrition-related knowledge also played a role; participants noted the importance of foods such as beans for anemia prevention. At the social environmental level, parents promoted healthy eating by providing advice on nutrient option and home-cooked meals. The concrete environment also influenced intake, with foods bachelor in schools beingness predominantly low-nutrient energy-dumbo. Macrosystem influences were evident, every bit adolescents used the Internet for nutrition information, which they viewed as credible.

Conclusions

To address diet-related issues such equally obesity and fe-deficiency anemia in Peruvian adolescents, further enquiry is warranted to elucidate the roles of certain factors shaping behavior, particularly that of family, cited numerous times as having a positive influence. Addressing nutrition-related bug such every bit obesity and iron-deficiency anemia in this population requires consideration of the effect of social and environmental factors in the context of adolescent lifestyles on beliefs. Nutrition pedagogy messages for adolescents should consider the cultural perceptions and importance of item foods, taking into account the diverse factors that influence eating behaviors.

Background

Adolescence is a time of transition in the lifespan. During this period, the physical, social and developmental changes that accept place play an important role in determining eating behaviors and health [ane]. Due to an accelerated growth rate and increased caloric needs, boyhood is a nutritionally vulnerable fourth dimension during which both dietary excess [2] and insufficiency [3, iv] and lack of variety and balance are common [5]. It is besides a period during which adolescents proceeds independence and select their own foods to a greater degree. Equally more independent choices are made, consumption of depression-nutrient energy-dense (LNED) foods may increase, with a consequent excess intake of added saccharide and fatty, and inadequate intake of micronutrients such every bit calcium, iron, zinc, and vitamins A and C [half-dozen]. The changes that occur during adolescence may contribute to the development of a number of nutrition-related issues that may have lasting furnishings throughout the lifespan [7].

As part of the development of interventions to address nutritional issues in adolescent populations, information technology is necessary to empathise contextual factors that influence eating habits. Boyhood is a period of susceptibility to a number of influences on nutrition. Story et al. nowadays a theoretical framework to empathise influences on behavior, which includes iv levels: individual (intrapersonal), social environmental (interpersonal), physical environmental (community settings), and macrosystem (societal) [1]. Individual influences include food preferences, constitute to be a stiff predictor of nutrient choices [viii, ix], and knowledge of why and how to consume healthily, which may or may not translate into healthful beliefs [10]. At the interpersonal level, peers play a big office in determining habits [xi], as does family [12, thirteen]. The physical surround too plays a part in influencing beliefs, with the school environment being of particular importance. A number of studies in children and adolescents have found positive associations betwixt the availability of LNED foods in schools and calorie intake from these items, as well as torso mass index [14–xvi]. At the societal level are media influences; several contempo studies in diverse adolescent populations have demonstrated associations betwixt excessive television receiver and calculator use and undesirable eating behaviors that may contribute to overweight and obesity [17, 18].

Low and heart-income countries represent an important surface area of focus in addressing nutritional bug in adolescents, as in that location has been a rising in non-infectious disease in many regions, while malnutrition persists [19–21]. A number of studies have been published examining influences on eating habits among adolescents in depression- and middle-income countries to inform the design of interventions to promote desirable health behaviors. In a study of students ages 13 to 15 years from four African countries, for example, Peltzer [22] identified several factors at the interpersonal level that proved to exist important for boyish health, including peer back up at school and parental supervision. In a study of Chinese adolescents examining weight-related perceptions and behaviors, Xie et al. identified influences at the societal level impacting behavior, such as exposure to Western media [23]. Researchers have also sought to elucidate the factors influencing wellness-related habits in low- and middle-income countries, however, previous studies take generally employed quantitative methods that may non account for civilization-specific influences on behavior. Enquiry using in-depth qualitative methods is lacking, and may farther elucidate the complexity of factors impacting adolescent health behaviors.

Research aiming to place influences on adolescent behavior within the cultural context is peculiarly relevant to Peru, a middle income country. Peruvian adolescents are at high nutritional take chances, facing issues such as overweight and obesity, anemia, and pregnancy during a flow of development. The prevalence of overweight in adolescents 15 to 19 years of age is 19.1 %, and the prevalence of obesity is 4.v % [24]. In women in this historic period group, 17.two % suffer from anemia, and 13.2 % already have at to the lowest degree i kid [24]. Women living in areas with high rates of anemia and undernutrition who get pregnant during adolescence are more likely to die or suffer complications during pregnancy and delivery [25]; similarly, overweight adolescents have increased risk of neonatal and perinatal issues [26]. While dietary deficiencies pb to anemia, at the same time dietary excess is leading to increasing overweight and obesity, a double burden of malnutrition that presents a challenge in terms of development of health-related interventions [24, 27]. In addressing the nutritional bug in Peru, interventions that account for the cultural context and culture-specific influences on behavior are needed. The objective of the current report is to proceeds insight into socio-cultural influences on eating in adolescence by conducting in-depth interviews with adolescents in periurban Lima, Republic of peru.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

Subjects were males (north = 8) and females (n = vi) xv–17 years in Canto Grande, a periurban shantytown customs in San Juan de Lurigancho, Lima, Peru, a district in the costal desert typical of the large sprawling densely populated periurban districts surrounding fundamental Lima. This is one of the poorer districts of Lima, in which most adults are employed in informal or low-paying jobs and are classified equally having depression socioeconomic status [28]. Overweight and obesity are common amongst adolescents here; in an examination of the weight status of 54 female and 34 male adolescents 13–17 years of historic period seen at the vaccine clinic at the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional in Canto Grande, a community within the district of San Juan de Lurigancho, 37 % of girls and 32 % of boys were found to exist overweight or obese, reflecting higher rates than at the national level (M. Penny, personal communication, January 28, 2015).

Participants were selected using a census of inhabitants in Canto Grande to yield a purposeful random sample. The sample was purposeful in that a specific subgroup of adolescents inside the broader boyish population in Lima was the focus. Adolescents 15–17 years of age living in the selected community were eligible for inclusion. Once those eligible to participate had been identified using the census, researchers selected participants at random, visited the homes of those selected, and invited each to participate. Female subjects who had previously been or were meaning were excluded, as the aim was to examine influences on typical eating habits in adolescence. The sample size was determined using the concept of saturation of conceptual categories, or the bespeak at which no new information was observed in the data [29]. This was achieved through an iterative procedure of information collection and review of the data until in that location was failure to uncover whatsoever new concepts in the interviews [xxx]. The beginning author constantly checked and rechecked the elemental codes and concepts in a back-and-forth interplay with the data [thirty]. While in that location is little evidence in the literature regarding the ideal number of participants to be included in qualitative studies, Guest et al. plant in a systematic documentation that saturation occurred within the first 12 interviews, providing further support for the sample size in the current study [31]. Parents provided written consent for adolescents to have function in the study, and the adolescents provided written assent (an affirmative agreement to participate in inquiry). Participants were compensated for their time with a pocket-sized figurer. The Research Ideals committee of the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional approved the study.

Procedures

The start author, who was trained in interviewing and had previous experience in qualitative data collection and analysis in depression-income Spanish-speaking populations, collected all data in the Spanish linguistic communication in participants' homes. Conducting interviews in this setting allowed participants to bear witness examples of food items mentioned during the interview if needed. A local research assistant accompanied the beginning author to take notes and tape the sessions.

Free list of foods and pile sorts

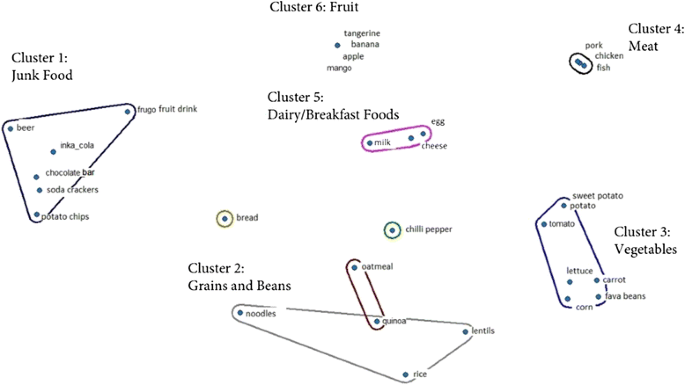

Free listing is a semi-structured interviewing method designed to identify the salient items in a defined category from the target population [32]. Four participants (2 male, 2 female person) were asked to name all nutrient items consumed in the area, at all times of twenty-four hour period, including condiments. In addition, foods included in a pile sort action in a previous study conducted in Peruvian adolescents in poor periurban communities were examined [33]. Ordinarily named items were selected to be pictured on a set of cards for use in the pile sort activity, with 14 out of 30 items matching those of the previous study [33]. Examples of items included were rice, beans, and milk (all items shown in the Fig. one). All food groups were represented in the prepare.

Results of multidimensional scaling and hierarchical clustering assay using pile sort data from adolescents ages 15–17 years (n = 10) in periurban Lima, Republic of peru

Pile sorts can be used to stimulate discussion regarding beliefs about food thus assuasive farther elucidation of influences on eating habits [32], and has been used extensively in research studies [33–36]. Unconstrained pile sorts were conducted with the remaining 10 (6 male, four female person) participants in the current written report. Pile sorting involved giving participants a set of 30 cards, each of which contained a singled-out food paradigm, and asking them to 'pile' cards into groups. The number of food images include reflect the recommendations of Blum et al., who suggest the use of 25 to thirty food images generated through the administration of the free list [37]. The same number of cards was used in a previous study in Peruvian adolescents, and items from all food groups were included to allow for sufficient items for formation of piles [33]. Participants were asked to group foods perceived to accept similar characteristics to form any number of piles. Later on group nutrient cards, participants were asked to name each 'pile' and describe the characteristics of the foods placed in that group. In another exercise, they were asked to order the thirty food cards from the about 'unhealthy' to 'good for you,' and to proper noun any other foods non pictured that they considered 'salubrious' or 'unhealthy.' Numbers written on each card were used to facilitate the recording of data from pile sorts and the 'ordering' exercise past paw during the interview.

Semi-structured interviews

Semi-structured interviews with all participants lasted approximately 60 min. The interview guide was devised by the first author through a review of the literature examining influences on eating in adolescents, and was then reviewed and refined by 2 co-authors with all-encompassing experience conducting enquiry in the Peruvian population. The guide was designed to arm-twist information on influences on eating at four levels identified in a previously adult theoretical framework: private (intrapersonal), social environmental (interpersonal), concrete environmental (community settings), and macrosystem (societal) [1]. This was achieved through the apply of questions addressing each level of influence on adolescent behavior, with examples of topics addressed at each level every bit follows: one) individual: nutrition-related knowledge, including strategies to prevent anemia; two) social ecology: activities with peers and family unit; three) physical environmental: neighborhood and nutrient environment in which eating behaviors occur; 4) macroystem: admission to Net and exposure to media through various types of technology, including cell phones and computers. A express number of questions related to influences on concrete activity habits were also posed (results not reported).

The first writer transcribed all audio-recorded interviews with participants verbatim, including the discussion that formed part of the pile sort activity.

Data analysis

Semi-structured interviews

Interview transcripts were analyzed using directed content assay [38], with the theoretical framework of categories of influence on adolescent eating serving to guide the analysis [one]. Directed content analysis involves using deductive categories to guide the coding of the text. This contrasts with coding that is generated inductively from the data [39]. Start with categories from the theoretical framework, the first author identified these primal concepts in the data to serve as initial coding categories [40]. With these categories, the first author coded each chunk of text using the NVivo software package version 10 (QSR International Inc., Burlington, MA, USA). Operational definitions were and so developed for each category based on the information. The initial coding, including both the coding schema and the actual coded text, was reviewed past two researchers with experience in qualitative analysis. The coding was discussed and refined amid the assay team, with the final coding scheme approved by all three researchers on the team. The process of checking and rechecking codes and concepts immune for data saturation to be accomplished with 14 interviews.

Pile sorts

Multidimensional scaling, which yields a map of items bundled in proximity to others to reflect groupings, and hierarchical clustering assay, which produces a refined graphic showing which items were nigh often grouped together [41], was completed with pile sort data using ANTHROPAC software (Analytic Technologies, Lexington, KY). The data assay for the qualitative comments participants provided as an explanation for the groupings was conducted using the same steps described above. The descriptions corresponding to each pile and comments about healthy/unhealthy foods were coded according to the aforementioned categories from the theoretical framework. Two co-authors and then reviewed and discussed the application of codes to the transcripts with the first author. The coding of the pile sorts categories was validated through review and discussion amongst the analysis team, using the same protocol equally the interview coding.

Validity of the data was ensured using the following strategies. The get-go was in developing the theory-informed coding scheme to identify the categories and code definitions [40]. The second strategy involved review of the coding scheme and coded transcripts by peer researchers who verified the codes and coding decisions for coherence. During this step codes were revised and agreed upon past the three researchers [40].

Results

From the pile sort analysis, six chief food item clusters were identified to reflect the results of the activity that required participants to group foods into piles according to whatever organization desired. When asked to depict the characteristics of the clusters of food items and assign a name to each group, participants provided the following responses: ane) junk nutrient (not-nutritive, tasty, expensive, chemical); 2) grains and beans (healthy, tasty, lunch foods); 3) vegetables (forbid affliction, natural); iv) meat (favorite, fat, comprise hormones); 5) dairy/breakfast foods (consumed daily, contain protein); 6) fruit (foreclose disease, contain vitamins). The results of the multidimensional scaling and hierarchical clustering assay are shown in the Fig. ane. The clusters identified are labeled, with the foods corresponding to each one shown in the Fig. 1.

When asked to rank foods pictured on the cards from least to nearly healthy, items such equally beer and hot pepper were generally placed first, followed by candy foods such as chocolates, soda, and potato fries. 'Whole' foods such every bit fruit, vegetables, beans, meat and dairy were often placed toward the 'healthy' end of the list, with 'quinoa' ranked equally the healthiest in several cases. Foods often mentioned as good for you but not pictured included legumes such as green divide peas, whole grains such as kiwicha, and fruits; unhealthy foods not pictured included loftier-carbohydrate processed foods such equally cookies and candy.

In examining responses from both semi-structured interviews and pile sort data, a number of influences on eating at the individual, social environmental, physical ecology, and macrosystem levels were identified. Key influences with exemplifying quotes are highlighted in Table ane.

Individual influences

Concerns about body paradigm

Participants, peculiarly females, mentioned concerns about body image and desire to appear 'thin' as affecting food choices. When asked about barriers to eating well, one female person participant said that some may not eat well because "they don't similar sure foods, or they say 'this nutrient volition make me fatty.'" Starchy foods such as bread, as well equally beans, were virtually commonly cited equally foods that may cause weight proceeds.

Financial resources

Participants as well mentioned lack of financial resources to purchase food, particularly when asked about barriers to salubrious eating. When describing what factors may prevent his peers from eating well, one male participant said, "Perhaps they don't have enough coin to exist able to consume well, or maybe their father leaves them money to exist able to cook and they spend it on other things, like games."

Nutrition-related cognition

Participants demonstrated knowledge both with regards to eating for maintenance of wellness and prevention of diet-related conditions, which may potentially influence behavior. Participants' clarification of 'eating well for health' reflected their familiarity with the concepts of moderation and residue. I participant described eating well every bit "non eating also much," and another cited the importance of "eating a balanced diet—not eating a lot of fat, starch, or sweets." There was as well mention of consumption of unprocessed foods; one participant said that healthy eating means "eating good, natural food, and very little processed or canned food." Some participants also mentioned the nutritional value of specific foods. As one participant put information technology, "salubrious eating ways eating dishes that have ingredients with vitamins, like fish, fruit, beans and vegetables." When asked about prevention of anemia, participants named foods such equally beans and fish every bit being of import in the diet. Others had less knowledge of valuable foods for anemia prevention, and mentioned the importance of the consumption of grains such equally wheat and kiwicha, while others cited non-dietary factors such as sleep and practice as being nigh of import.

Taste

In both the pile sort exercise and in interviews, participants identified the foods they perceived to exist 'tasty.' 'Junk' foods such as the Peruvian soft potable Inca kola (Coca-Cola Company, Atlanta, GA, U.s.) and other saccharide-sweetened beverages, crackers, and chocolate were oft identified equally foods pleasing to the gustation just also harmful in excess, a 'waste of money,' and 'non-nutritive.' When asked almost their favorite food and drink in interviews, many participants identified the seafood dish ceviche and soft drinks equally their preferences. In the pile sort action, when asked to name 'healthy' foods that they considered to be tasty, participants most often identified foods such as fruit, beans, milk and meat.

Social environmental influences

Family

Participants reported that their families' guidance helped them to make healthy nutrient choices; parents provided advice on food selection and fostered cooking skills. Parental advice was related to consumption of foods such as fruit, vegetables, and dairy products. In improver, parents advised participants to consume a multifariousness of foods and to limit LNED foods such as saccharide-sweetened beverages. Family unit members likewise stressed the importance of healthy, regular meals for disease prevention, and encouraged adolescents to eat foods prepared at home rather than purchased from street vendors. Adolescents reported helping their mothers to prepare dishes served at domicile, and in many cases were able to list the ingredients and quantities in recipes used.

Participants' families as well provided home-cooked meals. The majority of participants reported consuming all meals at abode, with the exception of foods consumed during breaks at schoolhouse. Most participants also reported eating meals in the presence of family members, well-nigh oft their mothers and siblings. Both adolescents and their mothers were responsible for serving nutrient prepared at abode; almost participants stated that their mother served them on at least some occasions at mealtime.

Peers

Comments revealed potential peer influences on eating. With peers, participants reported sharing LNED items such as carbohydrate-sweetened beverages and packaged snacks, specially during breaks at school. In some cases, a big bottle of soda was purchased to be shared among friends. Comments as well revealed potential peer influences on desired body size. When describing barriers to healthy eating, one participant said, "Some of my friends don't eat well because they don't accept enough coin or because they desire to look thin. My classmates only eat salad at lunch."

Concrete environmental influences

School

Many participants reported consumption of snack foods during the break at school. Foods bachelor for purchase were generally LNED items such as sugar-sweetened beverages and packaged snacks. In some cases, prepared food such as chicken soup and fried rice was also available for buy during the intermission. Participants who reported bringing their own snack to schoolhouse rather than purchasing more than often consumed items such every bit fruit.

Fast-food establishments

The bulk of participants reported consumption of fast food, such as fried chicken, French fries with sausage, hamburgers, and pizza. These foods were easily available for buy and in some cases were taken home to swallow. Among those who reported intake of fast food, frequency of consumption varied, with some participants reporting that they more commonly consumed these items on the weekend days, and others reporting daily consumption. When describing her weekend activities, 1 female person participant said, "On the weekend I stay at abode, assistance my female parent, watch television, and I buy French fries with sausage."

Convenience stores and street vendors

A number of products, particularly snack foods, were purchased from stores in the customs and street vendors. Participants reported purchasing items such as popsicles, toasted corn, chocolate, and soda. Similar to fast food, some participants mentioned that they more commonly consumed these items on the weekend days.

Macrosystem influences

Media

When asked to describe their daily routines, all simply iii participants mentioned the television and/or Internet as function of their schedule. Several participants mentioned that they had heard information about diet and wellness on television. The messages ranged in topic from wellness benefits of specific foods, to food safety, to limiting food waste.

About all participants said that computers interested them and that they used the Internet oft for both schoolwork and social activities. One female person participate noted, "I like to learn new things from the Internet, and play games. I utilize Messenger and Facebook." Another male participant said, "I go with my friends after school. It'southward fun to search for data, play games and sentinel movies and anime [Japanese animated productions]." All except one participant had used the Internet search for nutrition information and viewed Cyberspace sources as apparent. Ane female participant said, "I looked for information virtually a balanced nutrition. I institute out that fruit contains vitamins, and the foods that make upward a balanced diet are meat, chicken, eggs, milk and beans. I used Google, and believed this information because my instructor said information technology was right."

Word

To maximize the chance of success of nutrition pedagogy interventions, it is critical to consider the multitude of influences on adolescent eating habits. The current study employs a multi-method approach to provide insight into the factors that may accept an bear upon on behaviors of adolescents in periurban Lima, Peru. Study findings may guide future enquiry seeking to examine the influence of specific factors identified to inform programs aimed at improving dietary intake in youth.

Family was consistently described equally having positive influence on food habits and skills. Previous research in diverse populations of adolescents suggests that family meals may have benefits in terms of dietary intake, matted eating behaviors, substance use and psychosocial health [42, 43]. Other studies in the U.Due south. examining associations betwixt family unit meal frequency during adolescence and nutrition quality, meal frequency, social eating, and repast structure later in life betoken that family meals during adolescence may have a lasting positive influence on dietary quality and meal patterns in young machismo [44, 45]. Previous research in the U.S. has also shown that the protective event of family unit meals may be attributed to interpersonal factors, such equally healthy communication and parental positive reinforcement [46, 47]. Supporting family relationships as promising avenues to healthy eating may be key in improving dietary intake; nevertheless, studies are needed to farther examine the human relationship between familial factors and behaviors in Peruvian adolescents. Of note, a recent study in Colombian children and adolescents found that being office of an extended family predicted the likelihood of a child existence overweight or obese [48]. The authors note that extended family members may influence the behavior of youth, so that having someone such as a grandmother every bit a master caregiver may increment the likelihood of overweight [48]. Future studies in the Peruvian population may similarly involve examining the relationship betwixt family construction and bonds and eating habits. Barriers and facilitators with regards to family meals may be examined. Data may also be nerveless from parents and other caregivers to determine how they view their role in promotion of salubrious eating, provision of main meals at home, and the degree to which they serve as office models for adolescents. A contempo study conducted in Peruvian children points to the importance of examining parental modeling in this population, equally interviews with parents revealed that fathers or husbands sometimes brought domicile soda, and two mothers were "not able to live without soda" [49]. Additional studies on the influence of parents on the behavior of youth may inform interventions that target whole families as a means of improving dietary intake of adolescents.

Potential peer influences on eating habits were also identified. Adolescents reported consuming LNED items when they were with their friends. A contempo review of the literature indicates that peer influences on eating are widespread, and that in the presence of peers and friends, children and adolescents' energy intake increases [11]. Such results have been plant in adolescents in the U.Due south., with the presence of friends contributing to increased nutrient intake in youth [fifty]. Previous inquiry in Commonwealth of australia has besides suggested that adolescents' friends influence their intake of LNED foods over time [51]. In Peruvian adolescents, it may be of import not only to consider the role of peers in promoting intake of certain foods, simply likewise in addressing food insecurity. In a study exploring the lives of Peruvian adolescents in a low-income surface area outside of Lima, Bayer et al. written report one adolescent's business relationship of giving food to a friend who lacked economical resource [52]. Future studies may seek to elucidate the mechanisms of social influence on behaviors of Peruvian adolescents and to determine how peers may favorably or unfavorably influence intake, and whether there are differences in the influence of peers in male versus female social groups. In addressing unfavorable behaviors that may outcome from peer influence, grooming peer leaders to model and promote salubrious behaviors through teaching other youth how to modify behavior may be an effective strategy [53, 54]. A contempo study in adolescents in the U.South. focused on obesity prevention in the school setting through peer advocacy of salubrious eating suggests that interventions should actively involve all students in advocacy to promote salubrious behaviors [55].

In terms of macrosystem influences, the current study revealed that adolescents had frequent exposure to the television and Net. A recent written report also noted the large amount of television watching in Peruvian youth, with children watching equally early as when they wake upward in the morning, then during lunchtime (after returning from school), and then over again afterward completing their homework from five to 9 pm or 10 pm [49]. Adolescents in the current report fabricated utilize of the tv and Internet for a variety of purposes. Among these purposes was to obtain information related to diet, which adolescents uniformly viewed as credible. In designing nutrition instruction interventions, information technology is important to consider not only the frequent employ of engineering, but as well the degree to which adolescents trust the information gleaned from sources such as the television and Internet. To attain this demographic group, computers and mobile phones may be used equally vehicles for data delivery. A recent systematic review of mobile-phone based interventions for wellness did not identify whatsoever studies conducted in Latin America, revealing the paucity of enquiry in this area [56]. Technology may also be useful for data collection in interventions, as adolescents are expert in using electronic devices. The 'mobile nutrient record' is a new tool that may hold promise for dietary information collection in this population; this tool has been tested in adolescent populations in the U.S. with positive results [57, 58]. The role of the apace changing electronic information environs in influencing youth knowledge and wellness behavior is also important for diet educators to note, specially given the bonny and novel means technologies can deliver messages.

Since adolescents in Peru are more connected today through channels such every bit the Internet than they were in previous years [59], the influence of media images and letters on beliefs and behavior should besides be considered. In providing comments on various food items in the pile sort action, participants described meat every bit "fatty" and "containing hormones." Equally there is information readily available on the fatty in meat and its negative furnishings on the Internet and in newspapers and magazines, it is possible that these views were spurred by media messages. A number of studies in the U.S. [60–63], Canada [64], and Europe [65] have demonstrated that health information has a significant impact on consumer beliefs. The degree to which the media may influence Peruvian adolescents' views of specific foods as well as their eating habits should be examined in greater depth.

In addition, the potential media influences on the perception of ideal trunk weight may be further explored. Several participants mentioned that maintaining a low body weight was a priority among their peer groups. Previous studies have identified the media as 1 of the main purveyors of letters about the ideal body to youth, with thinness promoted in girls, and a muscular body considered ideal in boys [66–68]. While the media has been found to have a strong influence on body image perceptions of adolescents' in Western nations [69], however, more research is needed to determine whether it may have a similar influence on diverse populations of adolescents in Latin America. In a study exploring the attitudinal and perceptual dimensions of trunk paradigm amid adolescents in vi countries in Latin America, the authors speculated that frequent exposure to media-portrayed images of slender female bodies may have led to the strong appreciation for the thin female person body observed in the report [lxx]. A study of Chilean adolescents, however, revealed that although girls reported higher perceived pressure from the media to lose weight than their male counterparts, media influences did not significantly contribute to their weight loss behaviors [71]. Additional studies to make up one's mind the effects of media on beliefs in Peruvian adolescents are warranted. If the media is constitute to take a significant influence on body image and weight loss behaviors in this population, implementation of programs seeking to promote media literacy, such every bit the interactive wellness program "In Favor of Myself" recently conducted in Israel [72], may be explored.

Of note, participants often reported computer use as a social activity, and often went to Internet cafes with friends to listen to music, chat or play games. Some cited the utilize of social media sites such as Facebook during their time online. The social nature of Internet use in adolescents may have of import implications for development of interventions to accost nutrition-related concerns. In delivering nutrition education messages, development of multi-player games may be an attractive pick; interactive activities may also exist incorporated, such every bit discussion groups with peers. Social media may also prove to be a useful tool in conveying information. A recent review of school-based Internet obesity prevention programs for adolescents in the U.Due south. and Europe indicated the majority were successful in reaching loftier risk students and irresolute behaviors in the curt-term [73]; future studies may investigate the usefulness of such programs in the Peruvian population.

In addition to the influence of media on beliefs, nutrition education messages conveyed in school or elsewhere may also take an bear upon. Adolescents' groupings of foods in the pile sorts activity reflected current educational messages presented to school-age children, while comments during the activity revealed a host of factors affecting food choices. One current diet-related resource bachelor to school-aged children is the discolonchera escolar, a disc-shaped graphic accompanied by a manual that presents examples of salubrious lunches and an explanation of the health benefits of each of the food groups [74]. While participants frequently grouped foods based on 'type', such every bit grains or vegetables, as presented in the discolonchera escolar, they likewise categorized foods based on likes/dislikes, frequency of consumption, eating occasion, taste, toll and effect on health. In describing the categories, the concept of moderate consumption emerged too every bit recommended consumption of foods such equally fruit, vegetables, beans and whole grains. The nutrition pedagogy letters to which adolescents are exposed may affect food choices, along with a host of other factors at each of the 4 levels of influence on beliefs.

Limitations

Limitations of the current study include the individual unit of measurement of analysis examined in data collection. Through examination of perspectives of other individuals playing a role in influencing adolescent behaviors, such as parents, a clearer movie of the influences beyond the private level may have emerged. At that place was limited mention of several issues that may have potentially important impacts on behavior, such every bit eating disorders. It may have been useful to address such issues more specifically in the interview guide, and to have allowed more time for an in-depth discussion of such topics. Other techniques, such as focus groups, could also potentially be used to get together more detailed information on pertinent bug, such as peer influences. Qualitative studies using focus groups in other adolescent populations have explored meanings of thinness, dysfunctional eating, and body dissatisfaction, with implications for prevention of eating disorders, which are common in this age grouping [75, 76]. Future studies in Peruvian adolescents might involve collection of more in-depth information on additional behavioral influences on eating of importance identified in these preliminary studies and other information collection methods such as focus groups. A future study may too further examine influences on physical activity, an important health-related behavior. Due to time constraints in interviews, limited questions were posed on this topic and results are not reported. An boosted limitation was that participants were recruited from only one periurban region in Peru. These large periurban areas are habitation to virtually one tertiary of the population of Lima of 8 one thousand thousand inhabitants, and most take expanded through migration from rural areas [77]. Notwithstanding, the restriction to one community in ane of the periurban districts inevitably yields limited diverseness amongst the respondents, and it is possible that some of the views of the participants were specific to the surface area under study. Despite these limitations, this report did allow for identification of key socio-cultural influences on beliefs in an understudied grouping of adolescents, with implications for evolution of programs to accost diet-related issues in Peruvian youth.

Conclusions

Further research is warranted to provide more item on the roles of the factors identified in this research that shape behavior, particularly that of family unit. Future studies may involve examining the human relationship between family structure and bonds and eating habits. Addressing nutrition-related issues such as obesity and iron-deficiency anemia in this population requires consideration of the outcome of social and environmental factors in the context of adolescent lifestyles on behavior. Nutrition education messages for adolescents should consider the cultural perceptions and importance of particular foods, taking into account the diverse factors that influence eating behaviors.

Abbreviations

- LNED:

-

Low-nutrient energy-dumbo

References

-

Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French Southward. Private and ecology influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(3 Suppl):S40–51.

-

Mendez R, Grissom Thousand. Disorders of childhood growth and development: childhood obesity. FP Essent. 2013;410:20–4.

-

Micali N, Ploubidis G, De Stavola B, Simonoff E, Treasure J. Frequency and Patterns of Eating Disorder Symptoms in Early Adolescence. J Adolesc Wellness. 2014;54(5):574–81.

-

Lask B, Bryant-Waugh R: Eating disorders in childhood and adolescence: Routledge; New York, NY. 2013.

-

Ochola S, Masibo PK. Dietary intake of schoolchildren and adolescents in developing countries. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64 Suppl 2:24–twoscore.

-

Lachat C, Nago E, Verstraeten R, Roberfroid D, Van Camp J, Kolsteren P. Eating out of dwelling and its association with dietary intake: a systematic review of the bear witness. Obes Rev. 2012;xiii(4):329–46.

-

Dwyer J. Starting downwardly the right path: nutrition connections with chronic diseases of afterwards life. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(ii):415S–20.

-

Di Noia J, Byrd-Bredbenner C. Adolescent fruit and vegetable intake: influence of family support and moderation past home availability of relationships with afrocentric values and taste preferences. J Acad Nutr Nutrition. 2013;113(vi):803–8.

-

Brug J, Tak NI, te Velde SJ, Bere E, de Bourdeaudhuij I. Taste preferences, liking and other factors related to fruit and vegetable intakes among schoolchildren: results from observational studies. Br J Nutr. 2008;99 Suppl 1:S7–14.

-

Spronk I, Kullen C, Burdon C, O'Connor H. Relationship between nutrition cognition and dietary intake. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(ten):1713–26.

-

Salvy S-J, de la Haye K, Bowker JC, Hermans RCJ. Influence of peers and friends on children'due south and adolescents' eating and activity behaviors. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(3):369–78.

-

Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors amid children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(three Pt 2):539–49.

-

Savage JS, Fisher JO, Birch LL. Parental Influence on Eating Behavior: Conception to Adolescence. J Law Med Ideals. 2007;35(1):22–34.

-

Pull a fast one on MK, Dodd AH, Wilson A, Gleason PM. Association between school food surroundings and practices and trunk mass index of US public school children. J Am Nutrition Assoc. 2009;109(2 Suppl):S108–17.

-

Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C, Wilson A, Gleason PM. Schoolhouse food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of United states of america public schoolhouse children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2 Suppl):S91–107.

-

Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Story Chiliad. Schoolwide nutrient practices are associated with body mass index in heart school students. Curvation Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1111–4.

-

Rey-López JP, Vicente-Rodríguez Grand, Répásy J, Mesana MI, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, et al. Food and drink intake during television viewing in adolescents: the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) study. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(ix):1563–9.

-

Shi 50, Mao Y. Excessive recreational computer use and food consumption behaviour amid adolescents. Ital J Pediatr. 2010;36:52.

-

Alwan A, MacLean DR. A review of non-communicable disease in low- and center-income countries. Int Wellness. 2009;i(1):iii–nine.

-

Popkin B. Global changes in diet and activity patterns as drivers of the nutrition transition. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program. 2009;63:ane-iv.

-

Rivera JA, Pedraza LS, Martorell R, Gil A. Introduction to the double burden of undernutrition and excess weight in Latin America. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(6):1613S–half dozen.

-

Peltzer K. Health beliefs and protective factors amongst school children in four African countries. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16(2):172–80.

-

Xie B, Chou C-P, Spruijt-Metz D, Reynolds G, Clark F, Palmer PH, et al. Weight perception and weight-related sociocultural and behavioral factors in Chinese adolescents. Prev Med. 2006;42(3):229–34.

-

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica east Informatica. Encuesta Demografica y de Salud Familiar 2012. Lima, Peru: (DHS) INEI; 2013.

-

Scholl TO, Hediger ML. Anemia and fe-deficiency anemia: compilation of information on pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59(2 Suppl):492S–500. discussion 500S – 501S.

-

Sukalich Southward, Mingione MJ, Glantz JC. Obstetric outcomes in overweight and obese adolescents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(iii):851–five.

-

Chaparro MP, Estrada 50. Mapping the nutrition transition in Peru: evidence for decentralized diet policies. Rev Panam Salud Pública Pan Am J Public Health. 2012;32(3):241–four.

-

Asociacion Peruana de Empresas de Investigacion de Mercados. Niveles socioeconomicos 2013 [Internet]. 2013. http://www.apeim.com.pe/wp-content/themes/apeim/docs/nse/APEIM-NSE-2013.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2015.

-

Flick U. An introduction to qualitative inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage; 2014.

-

Bowen GA. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: a research note. Qual Res. 2008;viii(i):137–52.

-

Invitee Yard, Bunce A, Johnson L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

-

Weller South, Romney A. Systematic data drove. Newbury Park: Sage; 1988.

-

Creed-Kanashiro HM, Bartolini RM, Fukumoto MN, Uribe TG, Robert RC, Bentley ME. Formative research to develop a nutrition education intervention to improve dietary iron intake among women and adolescent girls through community kitchens in Lima. Peru J Nutr. 2003;133(xi Suppl 2):3987S–91.

-

Cortes LM, Gittelsohn J, Alfred J, Palafox NA. Formative research to inform intervention development for diabetes prevention in the Republic of the Republic of the marshall islands. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28(half-dozen):696–715.

-

Quintiliani LM, Campbell MK, Haines PS, Webber KH. The utilize of the pile sort method in identifying groups of healthful lifestyle behaviors amongst female person customs higher students. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(9):1503–vii.

-

Caballero Hoyos R, Torres López T, Chong Villarreal F, Pineda Lucatero A, Altuzar González M, López CB. Cultural conceptions on dengue in urban contexts in Mexico. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;xl(i):126–33.

-

Blum 50. Community assessment of natural nutrient sources of vitamin A: guidelines for an ethnographic protocol. IDRC: Boston, MA. 1997.

-

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Assay. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

-

Hickey K, Kipping C. Issues in enquiry. A multi-phase arroyo to the coding of data from open-concluded questions. Nurse Res. 1996;4:81–91.

-

Potter WJ, Levine‐Donnerstein D. Rethinking validity and reliability in content assay. J Appl Commun Res. 1999;27(3):258–84.

-

Jackson KM, Trochim WMK. Concept Mapping as an Alternative Approach for the Assay of Open-Ended Survey Responses. Organ Res Methods. 2002;5(iv):307–36.

-

Fulkerson JA, Larson N, Horning Thousand, Neumark-Sztainer D. A Review of Associations Betwixt Family or Shared Repast Frequency and Dietary and Weight Condition Outcomes Across the Lifespan. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(1):two–19.

-

Neumark-Sztainer D, Larson NI, Fulkerson JA, Eisenberg ME, Story M. Family meals and adolescents: what take we learned from Projection Eat (Eating Among Teens)? Public Wellness Nutr. 2010;thirteen(07):1113–21.

-

Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Family meals during adolescence are associated with college diet quality and healthful meal patterns during young adulthood. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(9):1502–x.

-

Larson North, Fulkerson J, Story Thousand, Neumark-Sztainer D. Shared meals amid immature adults are associated with better diet quality and predicted by family meal patterns during boyhood. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(05):883–93.

-

Berge JM, Wall M, Larson N, Loth KA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Family unit Functioning: Associations with Weight Status, Eating Behaviors, and Physical Activity in Adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):351–7.

-

Berge JM, Rowley S, Trofholz A, Hanson C, Rueter K, MacLehose RF, et al. Childhood obesity and interpersonal dynamics during family meals. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):923–32.

-

Gonzalez-Casanova I, Sarmiento OL, Pratt One thousand, Gazmararian JA, Martorell R, Cunningham SA, et al. Individual, family, and community predictors of overweight and obesity among colombian children and adolescents. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E134.

-

Busse P, Díaz R. What are the tv viewing and eating habits of children in Peru? Glob Health Promot. 2014:1–11.

-

Salvy SJ, Howard G, Read M, Mele Due east. The presence of friends increases nutrient intake in youth. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(2):282–7.

-

De la Haye Thousand, Robins G, Mohr P, Wilson C. Adolescents' Intake of Junk Nutrient: Processes and Mechanisms Driving Consumption Similarities Among Friends. J Res Adolesc. 2013;23(3):524–36.

-

Bayer AM, Gilman RH, Tsui AO, Hindin MJ. What is adolescence?: Adolescents narrate their lives in Lima. Peru J Adolesc. 2010;33(4):509–20.

-

Mellanby AR, Rees JB, Tripp JH. Peer-led and adult-led school wellness pedagogy: a critical review of available comparative research. Health Educ Res. 2000;15(five):533–45.

-

Campbell R, Starkey F, Holliday J, Audrey S, Bloor M, Parry-Langdon North, et al. An breezy school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in boyhood (Assist): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1595–602.

-

Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Uyeda Grand, Hawes-Dawson J, Klein DJ, Schuster MA. Preliminary healthy eating outcomes of SNaX, a airplane pilot community-based intervention for adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(two):196–202.

-

Buhi ER, Trudnak TE, Martinasek MP, Oberne AB, Fuhrmann HJ, McDermott RJ. Mobile phone-based behavioural interventions for health: A systematic review. Health Educ J. 2013;72(5):564–83.

-

Daugherty BL, Schap TE, Ettienne-Gittens R, Zhu FM, Bosch M, Delp EJ, et al. Novel technologies for assessing dietary intake: evaluating the usability of a mobile telephone food record amongst adults and adolescents. J Med Net Res. 2012;14(2):e58.

-

Schap TE, Zhu F, Delp EJ, Boushey CJ. Merging dietary cess with the adolescent lifestyle. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2014;27 Suppl 1:82–8.

-

Lloyd CB. Growing Up Global: The changing transitions to machismo in developing countries. Washington: National Academies Press; 2005.

-

Adhikari M, Paudel L, Houston J, Paudel KP, Bukenya J. The touch on of cholesterol information on meat demand: Application of an updated cholesterol alphabetize. J Food Distrib Res. 2006;37:60–ix.

-

Kinnucan HW, Xiao H, Hsia C, Jackson JD. Effects of health information and generic advertising on U.S. meat demand. Amer J Agr Econ. 1997;79:13–23.

-

Capps Jr O, Schmitz JD. A recognition of health and nutrition factors in nutrient need analysis. Westward J Agr Econ. 1991;sixteen(1):21–35.

-

Miljkovic D, Mostad D. Impacts of changes in dietary preferences on U.Southward. retail demand for beef: Health concerns and the function of media. J Agribus. 2005;23(two):183–98.

-

Chang H, Kinnucan HW. Advert, information, and production quality: The example of butter. Amer J Agr Econ. 1991;73:1195–203.

-

Rickertsen G, Kristofersson D, Lothe Southward. Effects of health information on Nordic meat and fish demand. Empirical Econ. 2003;28:249–73.

-

Murnen SL, Smolak L, Mills JA, Good L. Thin, sexy women and strong, muscular men: Class-school children'southward responses to objectified images of women and men. Sex Roles. 2003;49:427–37.

-

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP, Lillis J. A longitudinal investigation of the evolution of weight and muscle concerns among preadolescent boys. J Youth and Adolesc. 2006;35:177–87.

-

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. Weight and shape concerns of boys and men. In: Thompson JK, editor. Handbook of eating disorders and obesity. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. p. 606–36.

-

McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. A prospective study of pressures from parents, peers, and the media on farthermost weight change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(five):653–68.

-

McArthur LH, Holbert D, Pena Yard. An exploration of the attitudinal and perceptual dimensions of torso image among male and female adolescents from 6 Latin American cities. Adolesc. 2005;40(160):801–16.

-

Mellor D, McCabe Grand, Ricciardelli L, Merino ME. Body dissatisfaction and body change behaviors in Chile: the role of sociocultural factors. Trunk image. 2008;5(ii):205–15.

-

Golan M, Hagay N, Tamir S. Gender related differences in response to "in favor of myself" wellness program to heighten positive self & body epitome among adolescents. PLoS One. 2014;9(iii):e91778.

-

Whittemore R, Chao A, Popick R, Grey 1000. School-based cyberspace obesity prevention programs for adolescents: a systematic literature review. Yale J Biol Med. 2013;86(1):49–62.

-

Instituto Nacional de Salud. Material Educativo: Discolonchera [Cyberspace]. 2007. http://www.ins.gob.pe/portal/jerarquia/five/387/material-educativo/jer.387. Accessed 18 June 2015.

-

Sharpe H, Damazer 1000, Treasure J, Schmidt U. What are adolescents' experiences of body dissatisfaction and dieting, and what exercise they recommend for prevention? A qualitative written report. Eat Weight Disord. 2013;eighteen(2):133–41.

-

Morris PF, Szabo CP. Meanings of thinness and dysfunctional eating in black South African females: a qualitative written report. Afr J Psychiatry. 2013;16(5):338–42.

-

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Estado de la Población Peruana 2013 [Cyberspace]. Lima, Peru; 2013. http://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1095/libro.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2015.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional in Lima, Peru.

Author data

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JB participated in the pattern of the study and study protocols, carried out the information collection in Peru, transcribed and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. OV and TD participated in the data analysis and helped to review and edit the manuscript. HC participated in the blueprint of the study and report protocols, helped to facilitate the data collection, and helped to review and edit the manuscript. MP conceived of the written report, participated in the design of the study and study protocols, helped to facilitate the information drove, and helped to review and edit the manuscript. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript.

Authors' information

JB is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Diet, Food and Creature Sciences at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. Her research interest is in improving dietary intake of underserved children and adolescents domestically and internationally and developing tools to assess food behaviors and dietary intake, specially in Spanish-speaking populations. Her previous work at the University of California, Davis involved the development of two tools, a food behavior checklist and concrete activity questionnaire, to exist used in the low-income Castilian-speaking customs in the U.S. to evaluate nutrition didactics interventions.

OB is an Assistant Professor of Social and Behavioral Wellness in the Department of Public Health at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, where she teaches courses in evaluation methods and health promotion program design. Her research focuses in the areas of household nutrient insecurity, social and ecology factors affecting dietary behavior in low-income communities, and the influence of extended families and social networks on dietary beliefs. She currently leads an evaluation research team that provides services to both the Hawaii Department of Human Services' SNAP-Ed programme, and Hawaii Department of Health's Salubrious Hawaii Initiative.

TD is an Assistant Professor of Public Health at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, where she trains in the outset of its kind Native Hawaiian and Ethnic Health MPH specialization. She holds a Bachelor's caste in nutrition from McGill University and is a registered dietitian in Québec. She completed her Principal's research in diet at McGill Academy's Middle for Ethnic Peoples' Diet and Environment (Cinematics), and has PhD in Public Health (Health Promotion) from Université de Montréal. Her inquiry is primarily community-based with Indigenous communities, uses participatory approaches and privileges Ethnic knowledge frameworks and addresses social perspectives of nutrient, public wellness and wellness promotion, food security, traditional nutrient systems, diabetes and obesity prevention, and aboriginal conceptions of health.

After obtaining an Chiliad.Phil. from University College, London, HC came to the Instituto de Investigación Nutricional in Lima, Peru in 1971 where she has conducted nutrition research ever since. Her inquiry has focused primarily on the diagnosis of the nutritional situation of infants and children (IYC) in underprivileged populations of Peru, and the development and implementation of nutrition intervention strategies to ameliorate infant, young child, adolescent girls and family feeding, diet and anemia in coastal, highland and pelting forest (Indigenous) communities. She has been involved in the evolution of manuals, guides and materials in these topics. She has considerable experience in applying formative research to pattern effective education-communication interventions.

MP is senior researcher and general director of the Instituto de Investigacion Nutricional (IIN) in Lima, Peru. She trained in Natural Sciences at the University of Cambridge (MA) and Medicine at the University of Birmingham (MBChB) and worked for vii years in Full general Medicine and Pediatrics in the Britain NHS before obtaining a Wellcome Trust Senior Inquiry scholarship to work on the microflora of the intestine of children with persistent diarrhea at the IIN. Afterwards completion of the scholarship she returned to Lima and has been resident since 1989. Her current areas of inquiry include man nutrition including dietary intakes, nutrition related beliefs; poverty and its relation to health and nutrition, overweight and obesity; public health including vaccine trials and health service research.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits unrestricted apply, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/null/1.0/) applies to the data made bachelor in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Banna, J.C., Buchthal, O.Five., Delormier, T. et al. Influences on eating: a qualitative written report of adolescents in a periurban area in Lima, Peru. BMC Public Health 16, forty (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2724-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2724-7

Keywords

- Child nutrition sciences

- Boyish

- Qualitative research

- Peru

- Latin America

kogageditaidown94.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-016-2724-7

0 Response to "Literature Review on Healthy Eating Habits for Adolescents"

Post a Comment